By using this website, you agree to our privacy policy

×Diary of a Letter Carver - The Apprentice Panel

by Tom Wiggins, our new apprentice

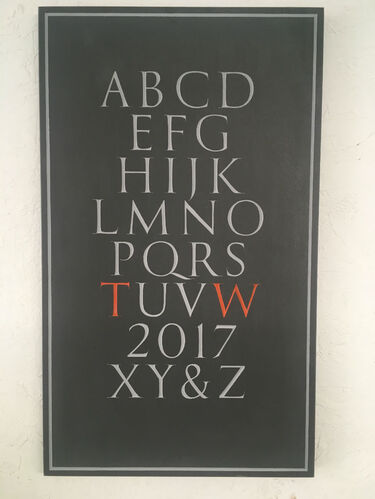

I began my apprentice panel on Tuesday 2nd May and all my focus – an extraordinary amount of focus – has been on that ever since. I noted in my diary last week that my apprentice panel has taken less time to carve than I thought it would – or rather, it hasn’t felt as long to work my way through it as I thought it would. When you live within the realms of a single letter for anything up to a day, it has a hypnotising effect. I really don’t know where May has gone!

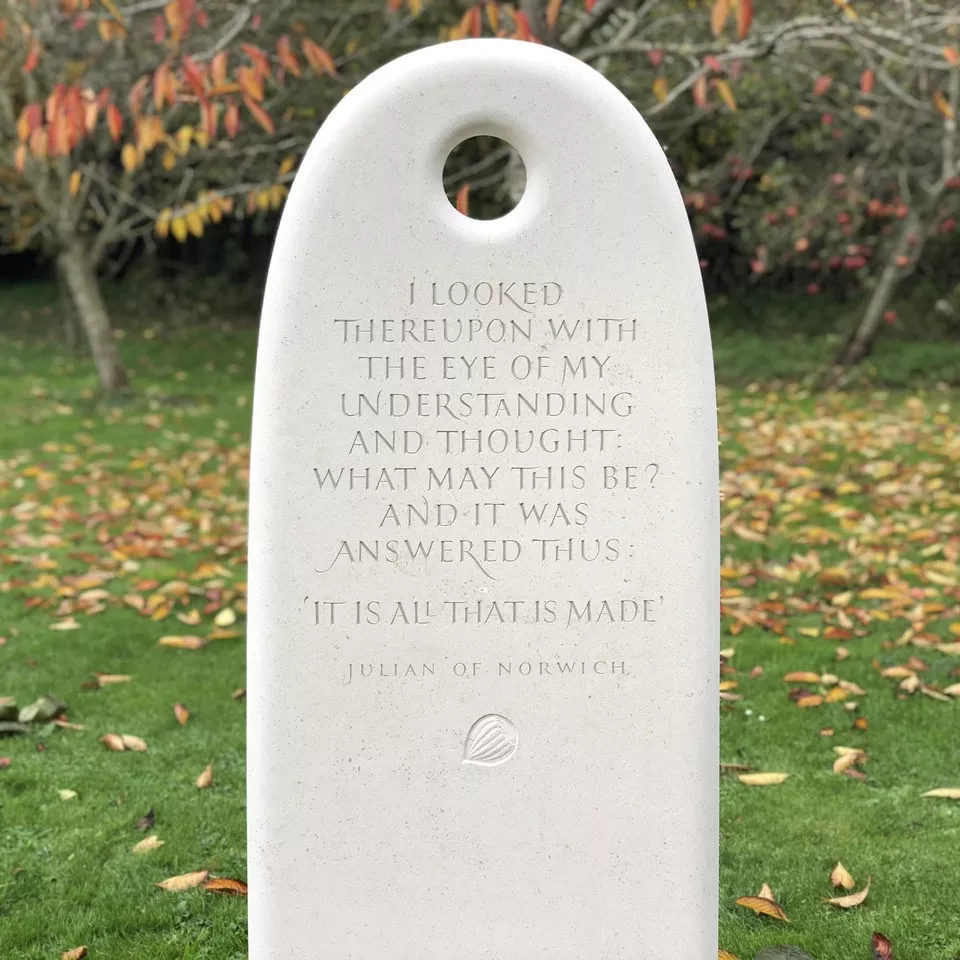

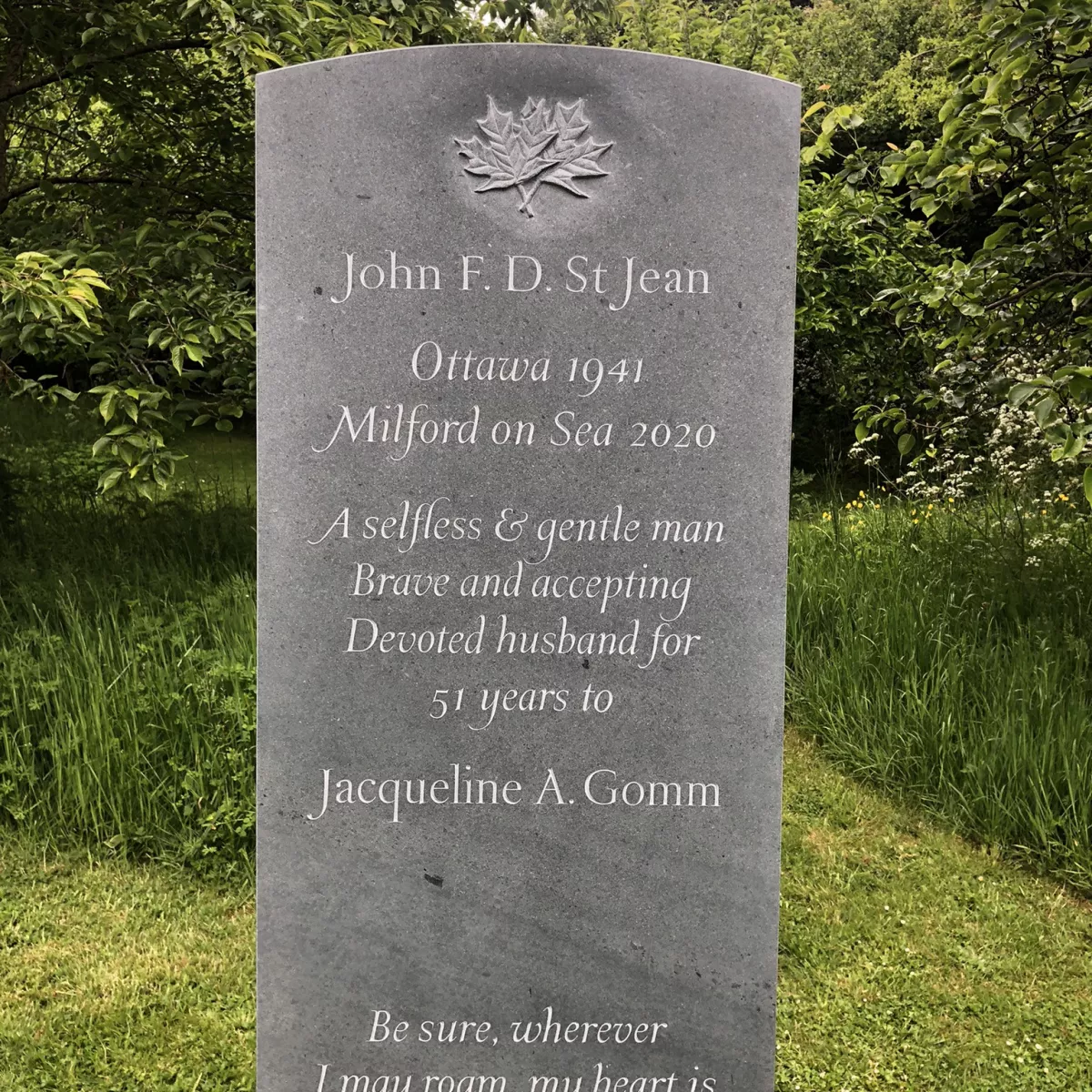

(For those who might not know, the apprentice panel is something that all apprentice letter carvers complete in the first three months of their apprenticeship. An alphabet in capitals is drawn on a stone panel (in my case, it’s Welsh slate, but there are various English limestones that suit the cut letter such as Portland, Hopton Wood and Tadcaster) as well as any additional bits of information. A common addition is the date, which I’ve included in my design for reasons of posterity. Then with the close supervision of the master carver, the apprentice gets to work. The panel traditionally stays in the workshop in which it was originally cut, even if the panel’s carver moves on.)

As I make my way up the panel (the letter carver always carves from bottom to top to prevent pencil lines lower down getting rubbed out by sleeves and/or falling dust), it hasn’t felt too fast or too slow. With the help of Fergus keeping an eye on my progress and having to rein me in every now and then (although it happens less frequently now), I’ve discovered that I’ve found my own pace. When I first started, Fergus was continually telling me to slow down. He was telling me that for my own good and the good of the letter. The more letters I carved, the more I found I respected the letters. And it’s through this respect for how they are formed that I’m developing an appreciation for the beauty of a finished letter. You attune to them. Without getting too fancy about it, they become your children and you really do want to do what’s best for them. Like children, it would be unwise to rush their development. There is no big secret: carving a beautiful letter takes practice, patience and time. To give you a sense of the rate of progress, I’m carving just over two letters (each one being 4cm high) per day as an average. Fergus would have been happy with one letter per day.

Before I started this apprenticeship, I assumed all letter carvers cut right to an accurate line, before proceeding onto the next letter. I thought the reason why so much emphasis is given to the drawing out process of letter carving was that the drawn letter had to be perfect. Not so. The experienced letter carver has an understanding of each letter in his or her head, the accuracy of which goes far beyond anything that can be drawn with a pencil on stone. Instead, the pencil lines act merely as guidelines. The drawing out is more for the purposes of getting the correct layout and spacing than for reasons of accuracy.

Instead of carving your v-cut right up to each line, Fergus has encouraged me to rub out the drawn lines as early as possible in the carving process. If you go too close to the line, they can start to deceive you. I can imagine this is especially the case when carving in slate because the lightness of a fresh cut (caused by the slate dust) is a similar light colour to the white pencil mark. By removing my pencil marks early, I’ve really had to be more cautious and really think about each letterform. To replicate it using your existing knowledge of a letterform, an example letter somewhere else in the workshop and your ticker tape (a small piece of paper used to mark the width of thick and thin lines so that those thicknesses remain consistent throughout any given piece) is the difference between using a Sat Nav to get somewhere and committing the route to memory before you leave the house. An over-reliance on lines is the lazy option.

To cut a letter from memory, to know your letterforms inside and out, is what being an accomplished traditional letter carver is all about.

Of all the things that I’ve learned while carving my apprentice panel, I’ve found that rubbing my lines out early in the carving process leads to a much greater overall awareness. I’ve felt my eye develop over the past few weeks and it’s mostly due to that. When I cut a letter to within the lines and then rub the lines out, the removal of these lines (along with the removal of some of the light slate dust from inside the V-cut) makes the letter look really rough. Then the process begins of perfecting that letter begins – and that means getting the thicks and thins to the right width, getting the entasis right; splaying the legs at the ends so the letter looks stable, making sure all the uprights look upright; sorting out any wobbles (although this should never be done to the detriment of a good thickness), getting the lowest point of the V-cut in the centre; getting the depth right. I could go on. There’s a whole myriad of things to consider, but that’s exactly why I’m loving every second of the process.

Fergus Wessel

Designer and letter-carver

Fergus created Stoneletters Studio in 2003, after training at the Kindersley Workshop. He is a member of the prestigious Master Carver's Association.

Request our free booklet today

- © 2024 Stoneletters

- Legal notice

- Privacy policy

- Disclaimer